Chapter 23: End of basic theory

End of basic theory!

Congratulations on making it this far! If your goal was to be able to write English text with steno, you’ve certainly achieved it!

From here on out, there are only about two or three more things you should be thinking about in your steno journey.

- Being comfortable with your own dictionary

- Writing shorter and building finger speed

- Switching to steno full time (optional)

This page will give a quick summary of how to achieve these 3 goals. Later chapters will discuss these in more detail, and are recommended that you read them. However, these chapters will be more like reference pages for you to read and check every so often.

Being comfortable with your own dictionary

Looking up words

English is a complicated language and it would be very difficult to create a theory that covers every single edge case. Furthermore, ensuring that a dictionary is complete and contains every single word is also practically impossible.

As such, you may come across words that are just impossible to write using the default Lapwing dictionary. This may be because it does not exist in the dictionary, or the theory is lacking rules that dictate how it should be written.

This is where Plover’s lookup tool comes in handy. If you are struggling to write a tricky word, don’t be afraid to just look it up. If several outlines show up in the lookup tool, I would first recommend trying the write-out entry which is the longest outline available. You can also identify the write-out entry as the one that follows theory rules. I will discuss later why you might want to look at any of the shorter outlines later.

Adding new words

If you’ve used the lookup tool and found that none of the outlines make sense, first try looking at any relevant pages and see if you’ve missed any theory. If you are on Discord, feel free to ask in the #lapwing-theory channel.

However, it is possible that these outlines aren’t covered under basic Lapwing theory—you’ve encountered a theory gap! At this point, you can decide to learn one of these outlines, or add your own.

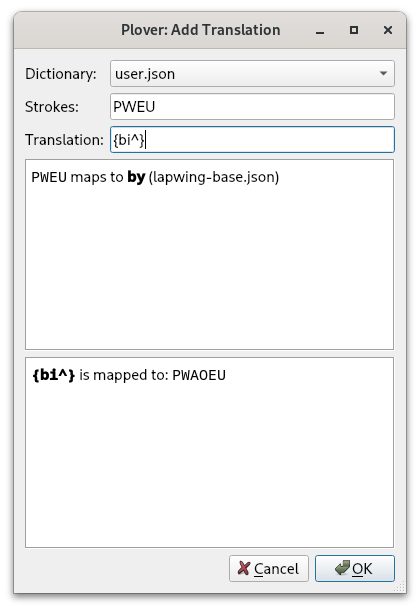

To add your own entry, stroke TKUPT to bring up the add translation tool. In the strokes field, start writing the outline you want to add. Then, move to the translation field by pressing TA*B and fingerspelling the word you want to add.

It is also very important that you don’t add new outlines to lapwing-base.json. If you intend to update the Lapwing dictionary, you will have to replace this entire file which will throw away any edits you have made.

An example of a theory gap

We know that prefix strokes generally take precedence over word strokes when there is a conflict. However, sometimes there are more than just one conflicting entry. Here are some examples:

| Word/prefix | Outline |

|---|---|

| bi- | PWAOEU |

| buy | PWAO*EU |

| by | PWEU |

| bye | PW*EU |

| Word/prefix | Outline |

|---|---|

| di^ | TKAOEU or TKEU |

| die | TKAO*EU |

| dye | TK*EU |

| Word/prefix | Outline |

|---|---|

| tri^ | TRAOEU |

| try | TREU or TRAO*EU |

At the moment, I have not thought of a consistent way of resolving these conflicts. This is one area where you may want to move around some outlines or come up with your own.

How do I build speed?

Practice

You need lots and lots of practice. At this point, it’s a good idea to try out sites that aren’t steno-specific. Personally, I spent about an hour or two everyday on typing sites like TypeRacer and Monkeytype after I had learned basic theory. 3 months of practice later, and I was frequently hitting 150 WPM on short TypeRacer quotes. on Monkeytype, I was reaching 180 WPM on the 60 second test.

Using these sites are a great way of increasing your finger speed. If you would like to track exactly how fast your finger speed is, I would recommend using a metronome. You can use an app on your phone or a website on desktop. Start the metronome at a speed that you can handle (say, 30 BPM) and try writing some material either through a website (like any of the ones linked) or just writing into a text document.

You can then gradually increase the tempo of the metronome until you find your maximum stroke speed. For me, I find this to be where going any faster results in a drop in accuracy. Three to four strokes per second (180 to 240 BPM) is quite fast and adequate for most hobbyists, though professional stenographers often reach five.

Some people have also found listening to music and stroking on beat quite effective. If you’re familiar with subdivision, you could get some effective practice even from slow songs.

Learning briefs

The other way of writing faster is by learning briefs. These abbreviated outlines are very nice because they allow you to increase your speed without having to move your fingers any quicker—you just have to be able to remember them! Obviously, it’s impossible to learn a brief for every single word, so how do you decide when you want to learn a brief?

This is highly personal, but I think a good starting point is whenever you run into a word that is awkward to write. To me, this includes words that have long outlines requiring your fingers to move a lot.

Here are some of the briefs I used in the last paragraph:

| Translation | Brief | Mnemonic |

|---|---|---|

| personal | PERPBL | personal |

| I think | SWR-PBG | Uses Jeff’s phrasing |

| whenever | WH-FR | The briefs of “when” + “ever” |

| you | U | |

| that is | THAS | |

| this | TH | |

| into | TPHAO | into |

| requiring | RAOEUR/-G | requiring |

| finger | TPEURPBG | -R folding |

| syllable | SEUBL | syllable |

Many of these might seem quite arbitrary, but that’s only because the you have not learned some of the techniques yet! Also, the process of memorizing briefs is quite a lot easier than you might think. Compared to, say, learning vocabulary of another language, learning briefs is much easier.

How to learn briefs

The easiest way to learn briefs is just by looking them up with Plover’s lookup tool. Whenever you feel like a word or phrase should be briefed, just look it up! Some people also like to learn briefs using Anki and plugins like plover-clippy-2.